An Analysis of Otherness and Horror

- Luca Pelo

- Jun 6, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 11, 2024

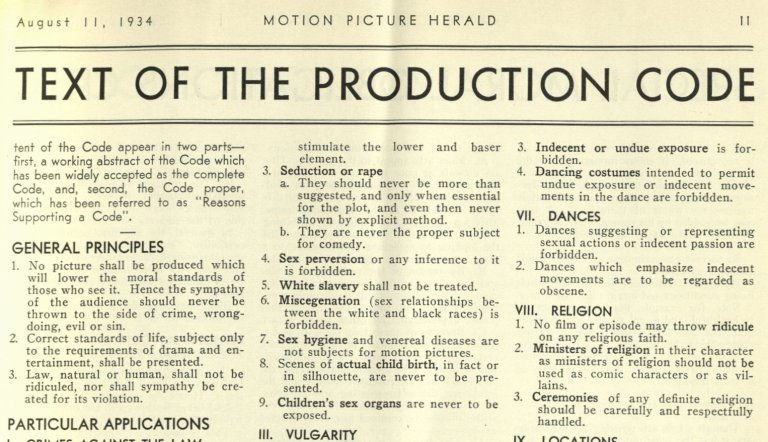

The horror film genre has always been an industry underdog. It was heavily restricted by the Hayes production code of the 1930’s-1960’s (Black, 1991), plagued with having the highest standards for critical rating, and not being taken seriously as a legitimate artistic presence within cinema since its inception. Despite its infamous tropes of sexualizing violence, punishing teenage sexuality, and greatly reinforcing the male gaze, it has also been a progressive powerhouse of the industry. It is known for commanding empathy for outcasts, tactfully exploring mental illness through metaphor, and making commentary on darker aspects of society that more well received genres would not dare touch for fear of conservative pushback. Naturally, these traits have historically made it a perfect platform for queer filmmakers to make bold statements about society’s cultural anxieties toward queer people, and to flesh out– even if thinly veiled by metaphor– very complex ideas about otherness, and misunderstanding, and acceptance.

In order to understand the trajectory of the queer community’s relationship with the horror genre, it’s pertinent that one understands the queer filmmakers who pioneered not just queer horror, but the horror genre at the most fundamental level. In 1931, a young English filmmaker named James Whale would adapt Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein into a feature film for Universal Studios. He would later adapt HG Wells’ The Invisible Man just two years later. Both films would portray topics of severe loneliness and alienation, but most importantly, of being treated as a monster. Around this time, Whale also met producer David Lewis, with whom he began living with in an openly gay relationship, for 23 years (BLC Museum, 2023). Whale is quite literally one of the founding fathers of horror as we know it today, and was publicly queer at a time when doing so was not only incredibly rare but also unbelievably dangerous. He showed the world that he was not afraid to be called a monster.

Decades down the line, queer filmmaker Don Mancini would write the script for Child’s Play (1988), a film that would introduce the world to Chucky, the foul–mouthed killer doll and satirical personification of misogyny and anger. It wasn’t until his first directorial effort, Seed of Chucky (2004), however, that Don Mancini would really start to explore queer ideas in the series. He did not tread lightly here either, with the entire premise of the film being about Chucky and his doll-wife reconnecting with their estranged child, who is struggling with their sexual identity. The couple bickers about the child’s gender in front of them, before the child asks “doesn’t what I want mean anything at all?” (Mancini, 2004). When asked what gender they would like to be, they explain, “ I'm not sure. Sometimes I feel like a boy. Sometimes I feel like a girl. Gasp Can I be both?” (Mancini, 2004). Eventually, their parents begin to refer to them as both Glen and Glenda, a direct reference to infamous B-movie director Ed Wood’s Glen or Glenda (1953), an early exploitation film and one of the very first instances of trans characters on the silver screen. It was riddled with problems and critically reviled, but is highly regarded in the cult cinema canon today. Like Wood, Mancini was widely panned by the film community, and he would go on to create a more traditional vision of Chucky for his next two feature films, an unfortunate and predictable consequence of queer people asserting themselves in 20th century media.

Around the same time as the release of Child’s Play (1988), openly gay English director Clive Barker would create a shocking and controversial body horror film called Hellraiser (1987), a no-holds-barred exploration of BDSM culture and sexual repression from a queer perspective. The film follows a woman who inadvertently opens a portal to hell through a mysterious puzzle box and subsequently meets the cenobites, a group of sadomasochistic demons who, in their own words, are “explorers in the further regions of experience. Demons to some. Angels to others” (Barker, 1987). A rule for watching Hellraiser is that if you think you know where it's going, you don’t. It’s not a demonization of fetish culture literally nor figuratively. Rather, it “deals with [themes of transgression, sexuality, and the body] in relation to notions of the monstrous 'Other', and more specifically, in relation to its portrayal of homosexuality and alternative sexualities” (Adams, 2017). Hellraiser, despite its provocative premise and low budget qualities, actually managed to fare well among critics and audiences alike. It's a rare success story of a queer filmmaker taking a chance on his audience and striking a vein. It also marks a turning point for a genre that would change the way that queer directors engage with corporeal topics: the aptly named “body horror”.

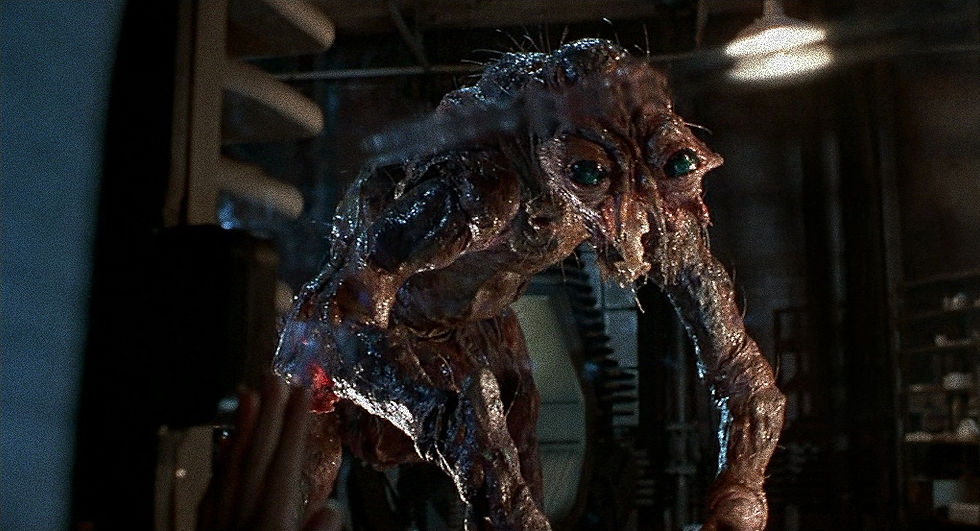

Body horror– defined as “a genre trope that showcases often graphic violations of the human body,” elicited in the form of “hybrids, metamorphoses, mutations, aberrant sex, and zombification” (Cruz, 2012). The genre– whose popularity is informally credited to horror master David Cronenberg– specifically grapples with the difficulties in accepting one’s physical form and more broadly, the discomfort of being

human. It doesn’t take a queer studies degree to instantly see the subgenre’s potential for dissecting trans issues from the brief description above. However, that doesn’t mean that it’s always been used that way for good. Films like Silence of the Lambs (1991), Psycho (1960), and Dressed to Kill (1980) all reinforce very harmful stereotypes about trans people, and much the horror they try to elicit around the topic is more shock and awe around trans existence rather than the horror of being queer in a society that gawks at and rejects you. As horror scholar Subarna Mondal describes it, these films “preoccupied with a simultaneous defiance and reinforcement of gender stereotypes. Fear of emasculation and /or the lure of it are explored through their treatment of the female body. The objectification of female bodies takes myriad forms in these films” (Mondal, 2021). While these films might portray queerness in a negative light, it’s arguably a good thing that they’re even talking about it at all. What I mean by that is that it demonstrated to future filmmakers how horror could be used as an outlet to talk about queerness in general, even if their messaging landed on the proverbially “wrong” side of the queer debate.

The beauty of body horror– or horror more generally– is that it doesn’t actually need to explicitly mention or portray queerness to tackle queer topics effectively. Films like Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986), Videodrome (1983) portray lost characters who undergo extreme physical and psychic alterations (one becomes an insect hybrid, the other, an indescribable monster) and have to grapple with the widespread stigma of their new bodies. In the end, they learn to cut ties with the past to truly accept themselves for who they are and be–quite literally– comfortable in their new skin. Similarly, Cronenberg’s later film Crash (1996) portrays finding a community that accepts one's sexuality, no matter how repulsively society reacts to it. Retrospectively, it’s quite clear that Crash was not about an underground community of omnisexuals being sexually attracted to automobiles at all. It was not just a provocative gag, but rather a demonstration of how the love and acceptance of a community can break through stereotypes and prejudices and allow people to take pride in their unique sexual identity.

A lot of horror follows this community acceptance trope, whether its a lone vampire joining a coven, a werewolf finding their pack, or in the case of The Craft (1996), a teenage witch finding a clique that would accept her for who she was, even if that group eventually tried to punish her for not fitting their idea of what a witch should be. “Excuse me, but I've spent a big chunk of my life being a monster and now that I'm not and having a good time, I'm sorry that bothers you,” asserts Bonnie, one of the witches, in a quote that sums up the attitude of the film quite succinctly (Fleming, 1996). It's unsurprising that The Craft has been recently reassessed as an important component of the sapphic film canon, being such a complex exploration of bigotry and oppression within the queer community.

Today, queer horror is a staple of popular media, and it's finally beginning to be taken seriously nearly a century after James Whale released Frankenstein (1931) and changed cinema forever. Even previously panned films such as Jennifer’s Body (2009) and A Nightmare on Elm Street 2 (1985) are garnering long-deserved recognition by critics and audiences alike for their queer-coded storylines, and the LGBTQA+ community is beginning to reclaim the genre. Of course, horror is far from perfect, and the same harmful tropes and angles remain in films to this day (if to a lesser extent): the objectification of queer bodies, the male gaze, and treating sex as a punishable sin.

However it seems that the genre, once divided between conservative fear-mongering and reverence for outcasts and “weirdos”, has finally settled into its skin, so to speak.

Works Cited

Adams, M. R. (2017). "Clive Barker’s queer monsters: Exploring transgression, sexuality, and the other". In Clive Barker. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press. Retrieved Sep 3, 2023, fromhttps://doi.org/10.7765/9781526122070.00016

Barker, C. (1987). Film Futures.

Black, G. (1991). Movies, Politics, and Censorship: The Production Code Administration and Political Censorship of Film Content. Journal of Policy History, 3(2), 95-129. doi:10.1017/S0898030600004814

BLC Museum. (2023, March 1). Behind the lens: The story of James Whale. Black Country Living Museum. https://bclm.com/2023/02/16/james-whale/

Cruz, R. (2012). Mutations and Metamorphoses: Body Horror is Biological Horror. Journal of Popular Film and Television. 40. 160-168. 10.1080/01956051.2012.654521.

Fleming, A. (1996). The Craft. Columbia Pictures. Mancini, D. (2004). Seed of Chucky. Rogue Pictures.

Mondal, S. (2021). Destruction, Reconstruction and Resistance: The Skin and the Protean Body in Pedro Almodóvar’s Body Horror The Skin I Live In. Humanities, 10(1),

Comments